Marcie Bronson

Curator

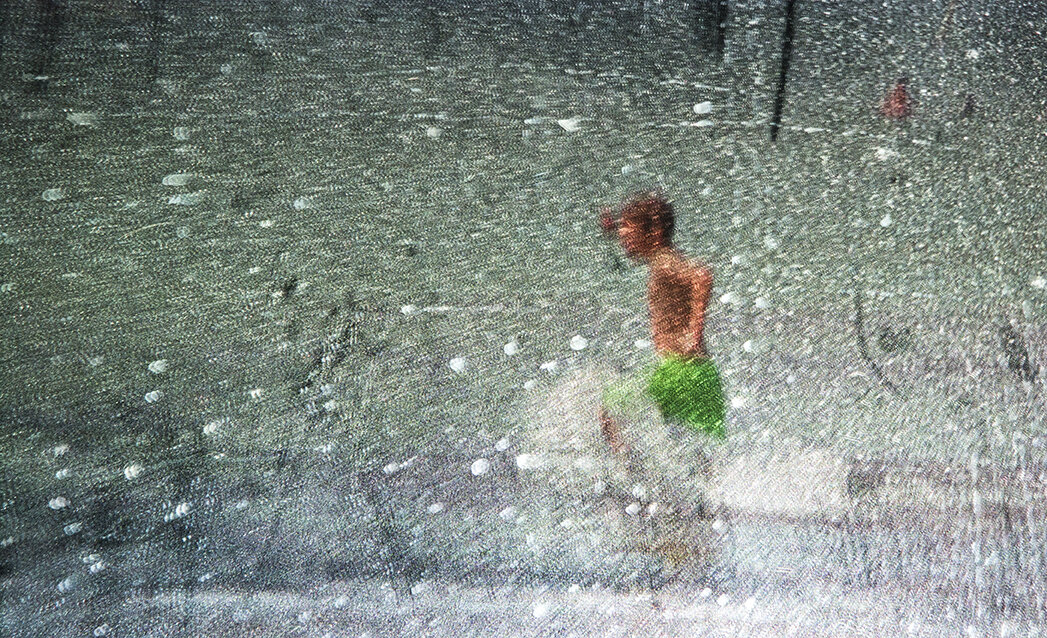

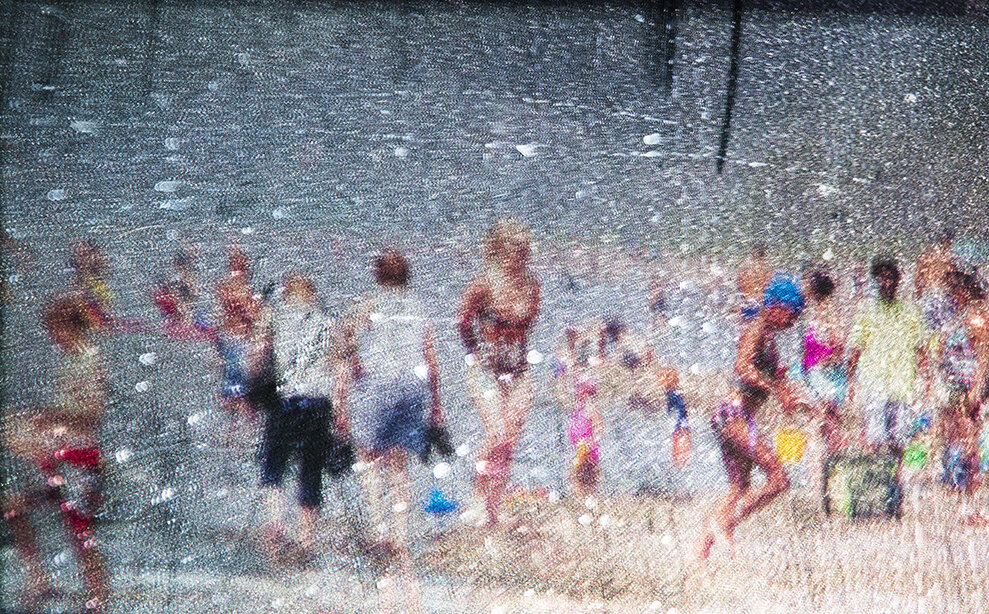

Inspired by a small, found archive of personal photographs, documents, and objects, Amy Friend presents a new body of work that considers how identity comprises both fact and fiction. Working from anonymous and family photographs and Super-8 films, Friend composes new images by manipulating and photographing abstracted excerpts of the original sources. Ambiguous and enigmatic, these images at once explore and confuse the histories they reference, suggesting new narratives from the minimal details they provide, and Friend uses this to reflect on how we understand and interpret the people around us. When anomalous threads appear and begin to unravel the fabric of stories we think we know, we call into question what is accepted as truth. So little can say so much, and even greater is the unexplored mystery of the spaces between what is known.

Rather than pursing the depiction of a concrete reality, Friend uses photography as a means of “exploring the relationship between what is visible and non-visible”. By engaging in a play of revealing and concealing that alludes to the mysteries her subjects harbour, Friend focuses our attention on certain elements while occluding others, nodding to the question of truth in photography, and the fiction inherent in our perception. As viewers, we draw inferences from subtle visual cues—a gesture, an object, an expanse of negative space—those of the artist’s design and those of her unknown collaborators. Yet, in reading these remnants, which have been extracted from their moment in history, our understanding is informed more by our own stories than by those of the depicted. Friend complicates this further through the titles of her works; some are drawn from notations on the original sources while others are fabricated, and they may suggest the personal, the collective, the mundane, or the grand.

Throughout her work, Friend references the history and science of photography, often by playing with light. For this suite of works, she photographed still and moving images projected on mirrors, and with the installation spanning the length of the gallery, she places us in her position. Friend’s role as a photographer is to record a scene, but viewing it through the camera lens, she is both there and not there. Caught between the silk photograph and the mirror, we struggle to apprehend what we see. Close looking at the image and its reflection offer different understandings of what is depicted and while we engage in a loop of double-takes, the image is never fully resolved, and we are always part of the picture.

Like photographs, objects tell a story, but only part of the story, and the answers they provide are outnumbered by the questions they pose. The collection of personal objects pinned above the mantel speak to the overlooked stuff of the everyday, while the more curious items and the letters and documents whose contents are hidden from view hold answers that might spur more questions. Friend notes that it is important to have curiosity about those lives we don’t know much about, observing that the identities of the anonymous are replaced by the stories we tell of them, both in, and after life.

Beguiling in their rich aesthetic and compelling imagery, Friend’s lush photographs and installations draw us in, and then complicate our experience of their beauty with an imperative to consider this moment and the fleeting sensations of life. At once weighty and illuminating, murky and buoyant, Friend negotiates the balance of human experience. As Friend describes, “These photographs and objects are fragments of everything and nothing.”